(photo credit: John Kulberg)

(photo credit: John Kulberg)

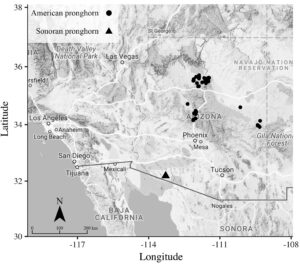

Pronghorn have been on the decline in Arizona for over a century due to over-harvest, habitat loss, and habitat fragmentation. Arizona is home to two subspecies of pronghorn, A. a. sonoriensis and A. a. americana. Population numbers of the endangered A. a. sonoriensis subspecies reached record lows in 2002 with an estimated 21 individuals remaining in the wild. Captive breeding efforts have rescued the subspecies from almost certain extirpation from the region and numbers have rebounded.

The A. a. americana subspecies has also suffered dramatic population declines, although to a lesser degree. Wildlife managers have not yet resorted to captive breeding due in part to the availability of transplant sources of relatively healthy A. a. americana populations in neighboring states. Repeated translocation of pronghorn from Montana, Colorado, Utah, and Texas has contributed to the rescue of several pronghorn populations in Arizona. However, the introduction of non-native genotypes to the area in concert with the persistence of strong barriers to pronghorn movement (roads & fences) is likely to have resulted in a patchwork of genetic population structure across the state.

The A. a. americana subspecies has also suffered dramatic population declines, although to a lesser degree. Wildlife managers have not yet resorted to captive breeding due in part to the availability of transplant sources of relatively healthy A. a. americana populations in neighboring states. Repeated translocation of pronghorn from Montana, Colorado, Utah, and Texas has contributed to the rescue of several pronghorn populations in Arizona. However, the introduction of non-native genotypes to the area in concert with the persistence of strong barriers to pronghorn movement (roads & fences) is likely to have resulted in a patchwork of genetic population structure across the state.

This project had two main aims. First, to assess population genetic parameters within and between the two subspecies to provide managers with up-to-date data that will inform them of the impact that management practices have had over the last several years. Second, to explore fine-scale genetic structure in A. a. americana relative to translocation history and physical barriers to gene flow.

We provided updated estimates of genetic diversity and relatedness to serve as a benchmark for future management toward further recovery of Sonoran pronghorn. We found that management of the captive population has upheld the distinction between the two subspecies in Arizona and stemmed further genetic diversity loss while avoiding an increase in inbreeding.

Read about our results in our 2021 paper in Conservation Science and Practice.